Following on from AAA’s decision, the United States Automobile Club became the sanctioning body for IndyCar. The major features of the period from 1956-1979 were the dramatic changes in car design and the move toward profitability.

What is the history of IndyCar racing?

IndyCar is an integral part of American sporting history. Beginning in 1909 and with one of the most famous flagship events in the world – the Indianapolis 500 IndyCar seems like an ever-present staple of the American sporting canon.

However, IndyCar is perhaps not as financially stable as it may once have been. In 2018, three races in the IndyCar series had no sponsor; in 2019, the Long Beach race will no longer be sponsored by Toyota.

This is especially worrying as the Long Beach race is the second most popular of the series, behind only the Indianapolis 500, which is helped at the famous Indianapolis Motor Speedway. To compound matters, Verizon will no longer be the title sponsor of the 2019 season, declining the renew their contract.

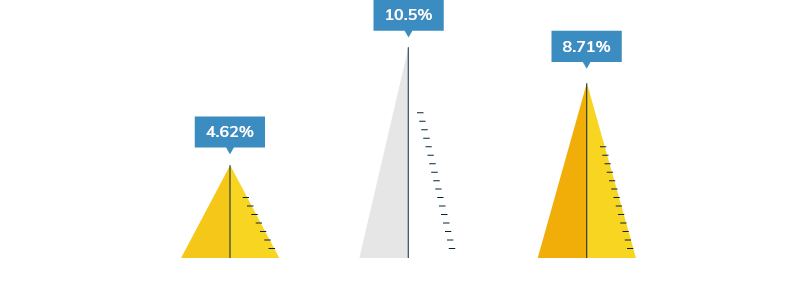

The sport is dominated by a fan base aged between 30 and 49, and many in the sport worry that it is failing to attract younger viewers. Indeed, as the chart below shows, the pickup rate amongst younger viewers is extremely low.

IndyCar is, therefore, skewing to an older demographic, which always worries the managers of a sport.

Share of Americans who watched any IndyCar Series event on cable TV in the last 12 months in 2018 (by age)

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/232042/any-indycar-series-events-on-cable-tv-usa/

However, IndyCar, in its previous incarnations has almost always suffered from some form of adversity, making it an incredibly resilient sport. Unlike the relatively straightforward path of comparable sports like Formula One and NASCAR, open-wheeled racing in the United States has seen changes in sanctioning bodies, the formation, and reconciliation of rival groups, and near-constant upheaval.

Its endurance is a testament to its popularity amongst its core supporters and the fact that it still retains a capacity to thrill.

1909-1955

The IndyCar series is as old as car racing in the United States, dating back to the earliest days of motoring. The first series of IndyCar ran from 1909 to 1955 and was run by the American Automobile Association (AAA).

- The very first IndyCar race was in Portland, Oregon in June 1909, and featured six cars, driving 14.6 miles around a track (three laps) with an average speed of 56 miles per hour.

-

- In its inaugural season, the IndyCar series consisted of 23 races – both street racing and dirt tracks. Indeed, as evidence of the nascent stage of the series, the final race was a 480 miles race from Los Angeles to Phoenix.

Indeed, it wasn’t until 1911 that the flagship event of the IndyCar series began – the Indianapolis 500 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Prior to that, races at Indianapolis were 50, 100, or 200 miles across a brick-lined rack.

The majority of tracks in the earliest days of the Indy series were wooden board tracks, although these were gradually replaced by concrete tracks as wooden boards became too expensive to maintain, particularly during the Great Depression.

The Depression and World War II both limited the schedule of the IndyCar series, with full series racing beginning again in 1946. In this period the cars and drivers got ever faster, and the racing became increasingly dangerous.

Ted Horn won three consecutive championships (1946-48) before fatally crashing in 1948. Following the Le Mans crash in 1955 in which Pierre Levegh and 82 spectators were killed, motor racing, in general, began a period of self-examination.

The American Automobile Association feared the result of such a crash in the IndyCar series for which it would be ultimately responsible. As a result, it refused to sanction any more races and removed its association with IndyCar.

1956-1979

A split in the 1970s between the USAC and the drivers was centered on how best to improve the financial status of the sport. For a brief period, the sport split, and a rebel CART (Championship Auto Racing Teams) emerged. However, by 1979 the two groups reconciled, and USAC reintegrated the CART.

In 1964, Parnelli Jones won the Milwaukee Mile in a Lotus Ford with the engine situated behind the driver. This quickly became the standard for all cars in the series, as the drivers felt that it provided the optimal combination of power and driveability. Furthermore, since 1970 all races except one have been won by cars with a turbo rather than an aspirated engine.

1980-2008

The defining feature of the period from 1980-2007 was the split, and eventual reintegration of the open-wheel championships, culminating in the modern IndyCar series.

Throughout the 1980s the financial state of the championship was strong, and the series was even able to attract drivers from the Formula One championship, with Jacques Villeneuve and Nigel Mansell being perhaps the most famous examples.

However, the original CART rebels never fully reconciled with the USAC, and the sport split again in this period to create the Indy Racing League (IRL) in 1994. CEO Tony George felt that the USAC series was becoming too similar to Formula One, with international drivers and a sport dominated by a small cabal of wealthy international manufacturers.

Furthermore, he believed that the sport was showing a lack of respect to the Indianapolis 500, which should be the premier event of the series. The IRL allowed only American drivers and manufacturers, raced only on ovals and held the Indy500 as its flagship race of the season.

In 2008, the two branches of the sport were reunited and took the name IndyCar to reflect the merger between the two.

2008-present

Since 2008, the IndyCar has put much of its acrimonious past behind it. Tony George was an early casualty, as the newly-merged organization sought a more irenic figurehead.

The period since the reconciliation has been dominated by the battle between Honda and Chevrolet. This competition has led to a rapid series of innovations, including the development of a new series of aero kits in 2015.

These aero kits allowed for a number of speed records to be broken; soon these became standard across the sport as a whole.

Financially, the sport is still recovering from the loss of fans during the split; it may never recover to its pre-1994 popularity. Ultimately, competition within the sport is better than competition between rival branches of the sport.

Safety Innovations

Safety is of paramount importance to the governors of IndyCar, and there has been constant innovation since the earliest days of helmetless, open-cockpit driving.

Since then, innovations in-car technology have been matched by developments in safety technology. Central to this is an understanding of how extreme speeds and extreme forces affect the body, better allowing for the engineering of safer equipment.

What is the impact on the body?

Traveling at 200 mph around tight bends means that there are extreme forces exerted on the body.

Throughout an IndyCar race, a driver will experience G-force loads of up to 5 Gs (meaning five times the normal effect of gravity on the body) when cornering, and between 0.7 and 1.5 Gs when accelerating. This places a strain on the driver’s body, particularly their neck.

IndyCar races also place other extreme stresses on the body, including extreme dehydration, a heart rate between 85 and 95% of maximum for the entire race, a body temperature of around 100 degrees, and blurred vision.

While these individually are not problematic, in combination they can diminish a driver’s capacity for safe driving and create long-term damage on their body. Accordingly, Indy Cars are designed to mitigate these as much as possible, with designs such as helmets that contain drinking water for drivers.

Furthermore, drivers are increasingly training their physical fitness to better handle the stresses of racing.

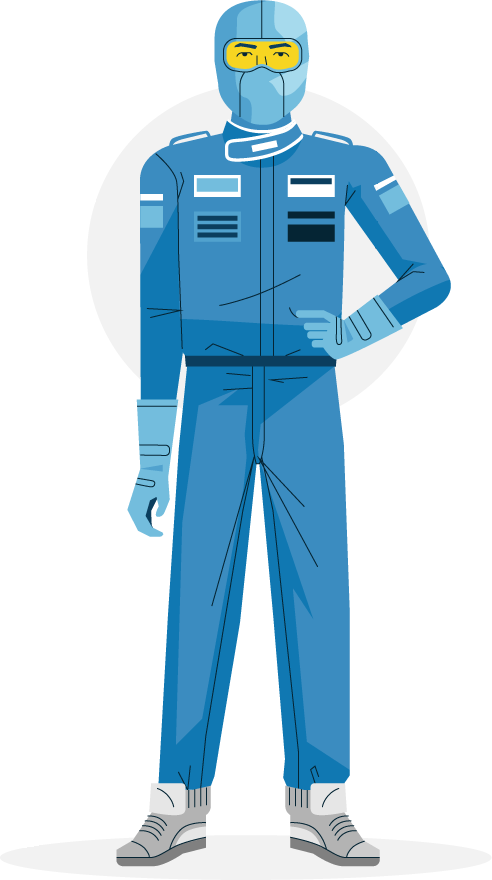

Nomex

Nomex is a high-performing heat-resistant material that is used in many parts of a driver’s suit. When Nomex encounters extreme heat, rather than melting, it thickens to form a more protective barrier over the skin.

Firesuit/ Underwear

Drivers wear a full-body, fire-resistant uniform that meets SFI 3.2A/5 or FIA 8856-2000 specifications. This specification standard is based on how well the suit protects drivers from heat and fire. Below the suit, is a Nomex suit/underwear that covers the entire body for better burn protection.

Feet

On their feet, drivers usually wear fire-resistant socks under shoes that are padded and fire-resistant as well. Driving shoes are usually leather or suede, lined with Nomex and a layer of padding, with rubber or polyurethane soles for grip.

Head sock

The head sock, which is made of Nomex, slides over a driver’s head and sits directly under the helmet. It is sometimes referred to as a balaclava.

Hands

The hands are protected by Nomex gloves, which usually have leather grips.

Head

and Neck

IndyCar requires that all drivers wear helmets and head restraints that meet or exceed FIA 8858-2010 certifications. Drivers are equipped with a helmet that has a carbon fiber exterior and a Nomex and impact-absorbing foam on the interior. More details on the safety features of the helmet are below.

Helmet

The helmet is one of the most important safety features for any IndyCar driver. They are tailored to each individual driver and are the result of constant safety innovation in the field. Each helmet contains at least 14 distinct safety aspects.

The helmet’s rigid outer shell is designed to disperse energy while also protecting it from an impact. Under the outer shell is an inner liner, which spreads forces across as large an area as possible.

Since 2003, it has been compulsory for helmets to be fitted with a small air bag that allows for safety crews to remove the helmet without neck strain. Under that, a lining made of Nomex and rayon transfers heat from the driver’s head, absorbs sweat, and protects the driver in case of fire.

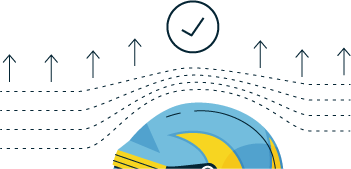

Aerodynamic features are also part of the safety setup of a helmet, as air is diverted away from the head to lower the force load on the neck. Neck protection is also tailored to the specific driver to ensure that the fit is as tight as possible.

Being fireproof is a major feature of the helmet, the neck strap, and the visor, and each is designed to protect the driver’s head in case of a serious impact, but also in terms of being trapped in a car on fire.

Head Restraint

The Head and Neck System (HANS) in use in IndyCar is compulsory and is designed to protect the driver from both head and neck injuries in the case of a sudden deceleration caused by a collision. As the diagram below shows, the head is rigidly connected to the neck via the helmet.

Collar

Sitting at the nape of the neck, the collar is designed to reduce the amount of movement and load experienced by a head and neck in a collision. An extension is sometimes added that allows the driver’s head to slide around and reduce the impact if they are rear-ended.

Tethers

These connect the collar to the helmet on both sides.

Shoulder Harness

This secures the driver at the shoulders.

The key feature of this system is the fact that the head cannot move totally independently of the body, even when under extreme forces caused by a collision.

This is one of the major causes of injury, even in relatively minor collisions. HANS is designed to still allow drivers range of motion when driving, although effectively extends the rigidity of the interior of the cockpit to the driver’s own body. The threshold for injury in the case of a collision is around 700lbs of force on the neck (in any direction).

The head restraint shown above limits these forces to less than 300 lbs; without it, a 40 mph crash exerts around 1,000 lbs of force, causing serious injury.

Safety Support

As well as the internal safety features for drivers, IndyCar has also taken great steps to provide safety features at all races.

There is a minimum of 18 attending medical personnel at every IndyCar race, made up of a trauma physician, an orthopedic physician, two paramedics, 12 firefighters/EMTs, and two nurses. These teams travel in four safety vehicles equipped with the latest medical equipment.

Read more: Buy Cheap Auto Insurance for Firefighters

In 2002, IndyCar mandated the installation of a SAFER barrier at the Indianapolis 500, and later at all other IndyCar races. The Steel and Foam Energy Reduction (SAFER) barrier provide a solid steel barrier, behind which is a series of foam joists.

The steel barrier provides a rigid force, and the foam underneath absorbs and disperses the impact, greatly reducing the forces caused by a collision, while also protecting spectators and staff located behind the barriers.

Further innovations center on stabilizing the vehicle, particularly aerodynamically, as well as using a combination of rigid and soft materials throughout the vehicles to better cope with the impact of a crash. IndyCar has had a symbiotic relationship with Formula One in this respect, and many innovations have been shared across the two sports.

The Indianapolis 500 rightly sits on the pantheon of great American sporting events, alongside the Superbowl and the World Series. However, unlike football and baseball, IndyCar’s future looks far from secure. However, this has always been true of open-wheel racing in the United States.

The innovations in both car speed and safety show a sport that is willing to invest in itself. The future for IndyCar may be less certain, but it is a sport that knows what it does well and is willing to spend money to continue to do that.

This is what has endeared it to successive generations of fans. After all, this is a sport that has been around for 45% of the entire history of the United States.

Sources and Further Reading:

- https://www.indycar.com/Fan-Info/INDYCAR-101/The-Drivers/Extreme-Conditions

- http://www.openwheelworld.net/indycar/series.php?id=37